The Cost of Partial Presence: Designing for Connection

What happens to a group when everyone is partially somewhere else… drifting through a digital landscape of notes, emails, and notifications?

I have been thinking about this question a lot recently. Sitting in leadership meetings, project teams, and even during one-on-one conversations. We routinely gather with phones on the table and laptops open, often treating this as a sign of efficiency. From a leadership perspective I have been wondering about the consequences. What does this do to our connectedness, our shared understanding, and our ability to think well together?

That curiosity led me to a colleague’s classroom, and to a problem she was wrestling with in her own teaching.

In a recent reflection on her teaching practice, Jessica Navarro, an Assistant Professor of Human Service Studies at Elon University, described noticing a growing disconnect between the kind of learning experience she was trying to cultivate and what was actually happening. She emphasized a classroom culture grounded in trust and mutual respect, where students were treated as co-creators of the learning environment. With that in mind, devices were permitted with the expectation that everyone would exercise discretion and consider how their behavior affected others.

On paper, this sounded like a strong, values-driven approach. In practice, it wasn’t working.

Phones appeared constantly. Not out of disrespect, but out of habit and social pressure. Jessica realized that individual intention was no match for the pull of an always-connected digital environment. The issue was not motivation, but the conditions under which learning was taking place. Something was interfering with the kind of presence her teaching depended on… the shared attention and responsiveness that make interactive, relationship-rich learning possible.

Rather than doubling down on rules, she went looking for a deeper insight, one that could help students understand why presence mattered in the first place. That search led her to a neuroscience study.

Storytelling & Synchronicity

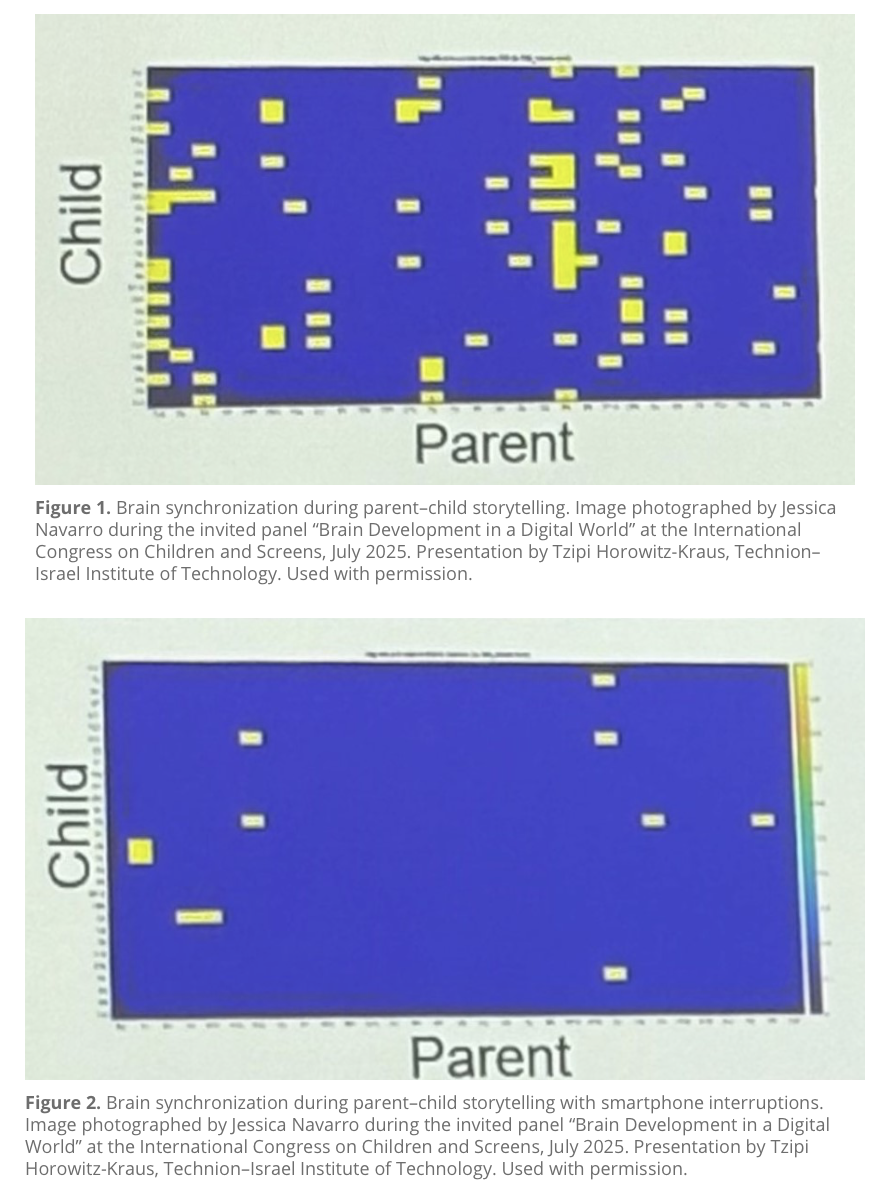

Jessica encountered research on parent-child storytelling at a conference that reframed the problem entirely. Using EEG technology, researchers observed what happens when parents and children read stories together in an interactive, dialogic way. During these shared storytelling moments, the brain activity of the parent and child became synchronized. Attention aligned. Processing aligned. Engagement aligned. Presence, it turns out, has a measurable neurological signature.

Then the researchers introduced a smartphone.

When parents received text messages during the storytelling interaction, that synchrony largely disappeared. The visual contrast was striking. Patterns of neural alignment faded into patterns of disconnection. The stories and people were the same. The only difference was the presence of a device that pulled attention elsewhere.

EEG images from a parent-child storytelling study illustrate the difference between shared attention and digital interruption. When parent and child were fully engaged in storytelling, their brain activity showed strong neural synchrony, visible as bright, aligned patterns across both brains. When a smartphone interrupted the interaction, that synchrony largely disappeared. The contrast makes visible what is easy to miss in everyday settings: attention is not only an individual state, but a shared one, and when it fragments, it reshapes the collective cognitive and relational space between people.

Jessica and I talked a lot about this. What I found fascinating was that it was not simply a matter of distraction, but something more profound. A collective consciousness, perhaps? The issue was not just that attention was being pulled away, but that the shared cognitive space between people was being fragmented.

Jessica brought this insight back to her students by sharing the research itself, including the brain images that made the impact of divided attention more visible. Rather than presenting a revised smartphone policy as a rule to enforce, she invited students into a shared understanding of what presence makes possible. The shift was intentional… and immediate. Phones stayed out of sight during class. This was a collective commitment to the desire for greater connection. If someone needed to use a phone, they stepped outside, but otherwise students focused on the flow of conversation. Jessica held herself to the same standard. Her goal was not compliance, but rather, a voluntary, shared decision to opt into being present.

Jessica told me that she came to view teaching as a form of dialogic storytelling. It is an ongoing exchange in which ideas are built together through listening, response, and shared attention. In this sense, teaching becomes a collaborative and facilitative process of spontaneously meaning-making in the context that the class is moving forward together both intellectually and relationally.

What makes this idea about partial attention so important is just how fragile shared presence can be. The research suggests that disruption does not have to be loud or intentional to matter. Even one person drifting off, scrolling on a phone, can quietly pull at the group’s shared attention in ways that are hard to notice in the moment, yet significant over time. The effect is not limited to the person who is distracted. It ripples outward, subtly changing the quality of connection and engagement for everyone else.

Attention & Teaming

Naturally, I began to consider this concept via a leadership perspective. If dialogic storytelling is vital to teaching, could it also be central to how teams function? Meetings, project groups, and committees are not merely venues for exchanging information… they are spaces and opportunities where people work together to make sense of complexity and to shape ideas collectively. They depend on shared attention, emotional attunement, quality interactions and idea integration, a healthy dose of spontaneity, a desire to build trust, and an ongoing accumulation of familiarity. In other words, they depend on synchronicity.

From that perspective, the neuroscience research becomes difficult to ignore. What happens to a team (or group) when attention is constantly fragmented? What does constant partial presence do to our sense of teamwork?

We often feel that we need our devices in meetings. We take notes. We look things up. We respond to emails. We constantly scan for urgent messages. For folks who constantly feel overbooked and overwhelmed, this kind of multitasking feels like effectiveness. Unfortunately, it might even feel necessary due to a high volume of tasks on our to-do lists. But what if it is actually doing harm, not just to us as individuals, but to our teams? What if constant partial attention is costing us camaraderie?

I am increasingly convinced that presence is not simply a personal virtue or an individual aspiration, but a collective condition shaped by the environments we create together. Jessica did not change the culture of her classroom by demanding better behavior or stricter compliance. She changed it by helping students see what was possible when attention was shared, and by redesigning the learning environment around those outcomes. By making the value of presence visible, she invited students to opt in to the conditions that allow groups to connect, learn, and ultimately thrive together.

That same insight extends well beyond the classroom. Leadership teams, project groups, and all-hands meetings are also forms of shared cognitive work. They are spaces where people are not only thinking together, but also building trust, shaping morale, and developing a shared sense of direction. When these spaces work well, there is clarity about what matters and a genuine feeling of moving forward together.

When constant partial attention dominates those moments, the effects are predictable. Alignment weakens, morale frays, and decisions lose depth. The cost is not always obvious in the moment, but it accumulates quietly and subtly over time.

Of course, being present is demanding. Sustained attention takes effort. Meetings can feel slow, repetitive, or only loosely connected to our immediate responsibilities. It is easy to drift, to check our phones, or to mentally step away when we feel bored, too busy, or only marginally involved. But the act of tuning out is not, neurologically speaking, neutral. Even if our direct participation feels inconsequential, it carries unseen (yet measurable via EEG scans) effects on the collective space, impacting how connected, coherent, and effective a group can be. When people are talking and others are scrolling, typing, or toggling between digital tasks, the social, relational, and cognitive experience of the group is degraded.

This research is pushing me to rethink how I host meetings and convene groups this year. What would it mean to design conversations and working sessions more intentionally, in the same way Jessica redesigned her classroom? In particular, I am interested in bringing this research directly into meeting agendas, sharing the underlying data and visuals, and inviting people to reflect together on what it suggests about how we work and think collectively.

Beyond Teams (library design?)

I have also been thinking about these ideas beyond leadership and meetings, and more broadly about library design. At a time when higher education is understandably focused on technology-oriented priorities such as data, AI, and digital infrastructure, it may be worth asking a counterintuitive question. What if one of the most valuable things libraries can offer is not acceleration, but intentional deceleration? I do not mean this as resistance to technology, but as a design choice that supports a different mode of thinking and connection.

I am increasingly drawn to the idea of a tech-free floor within a library, at least as a thought-experiment. In this sense, the library becomes an infrastructure for attention. I don’t imagine this simply a place for quiet study or concentration, important as those aspects are, but a more relational space where synchrony can emerge, conversations can deepen, and individuals and groups can experience a level of presence that is increasingly rare elsewhere.

This idea is directly informed by the neuroscience study Jessica encountered and by what she observed in her classroom. If shared attention can measurably strengthen connection and learning at the level of a pair or even a single group, it is worth wondering what might become possible at a larger scale? If reducing (removing!) digital interruptions can shift the dynamics of a single classroom, what might it do for an entire learning environment?

I imagine a library floor designed around this principle, not as a quiet zone or a collaboration zone in the usual sense, but as a commons space where multiple groups and individuals are engaging deeply at the same time. Some may be collaborating directly, others working independently or alongside friends on separate tasks. Each is engaged in their own work, yet collectively they generate a kind of intellectual and creative energy that compounds across the space. Attention and presence, even when indirect, become contagious. People feed off one another’s focus, momentum, and seriousness of purpose. Entering this floor is an intentional choice, an opt-in to a mode of working and being together that is increasingly difficult to find elsewhere.

Libraries are uniquely positioned for this kind of experiment. They are among the few places on campus explicitly designed for collective sense-making across disciplines, projects, and communities. Under the right conditions, they can become spaces where connection scales, where shared attention amplifies, and where something more powerful than individual productivity begins to emerge.

I know that it feels right now that many of our professional conversations are focused on AI, from literacy initiatives to ethical considerations. That work matters and there is so much we need to figure out. And yet, perhaps one of the most radical and valuable roles a library can play today is to be a place where presence and attention is deliberately designed and cultivated.

I am grateful to Jessica for sharing her classroom experiences with me. Her outcomes have encouraged me to rethink how I convene meetings and, more ambitiously, how we might design spaces where our communities can connect more deeply, think more clearly together, and engage in the kind of shared sense-making that our work today increasingly demands.